Bill Owens & the Suburbanites of Death

Bill Owens 1973 monograph Suburbia was more than a document of middle class America. While the United States and its corporate sponsors used Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia as proving grounds for emerging technologies and counterinsurgency tactics, housing developments began to reshape the Bay Area to support the growing defense industry.

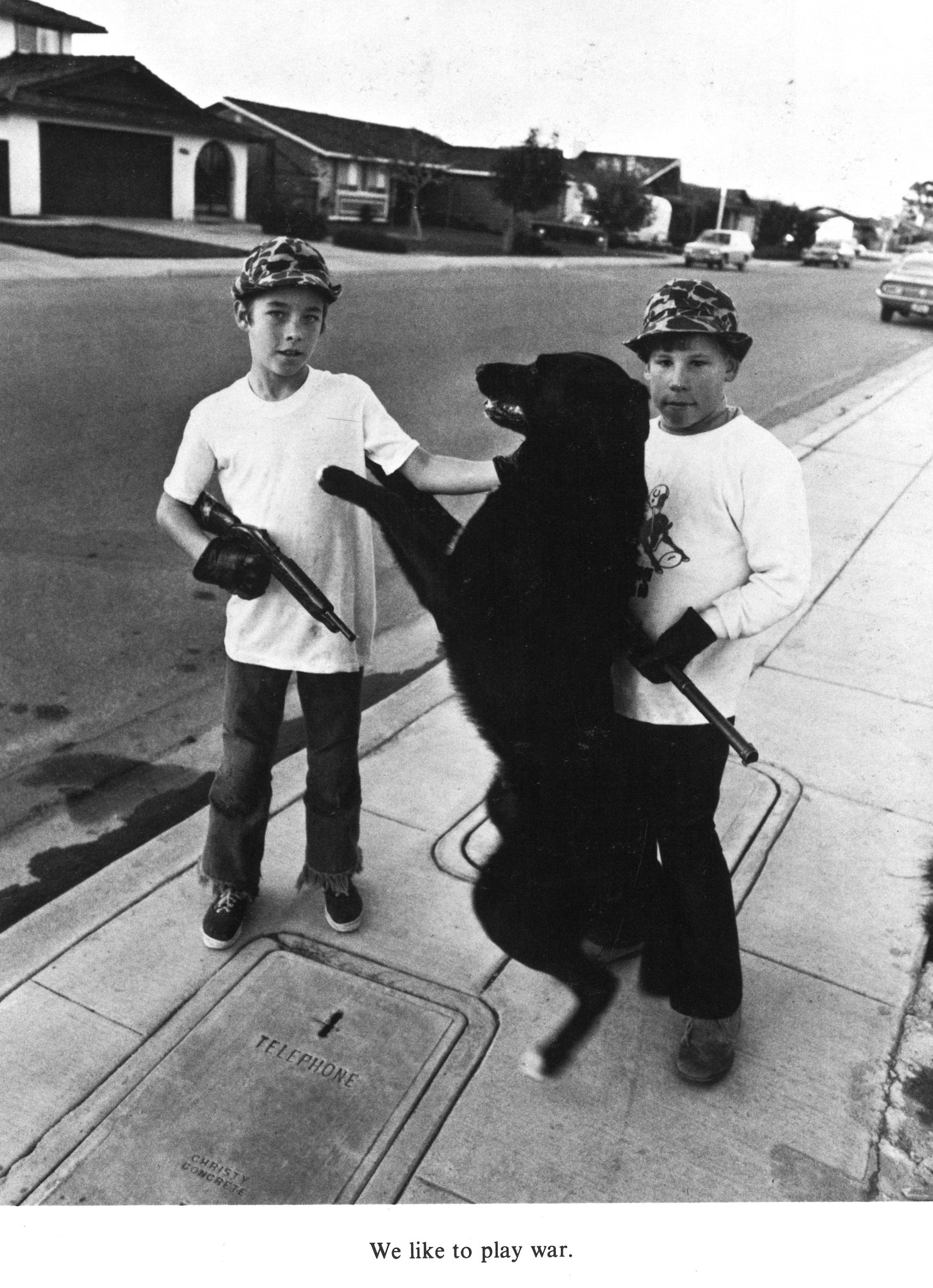

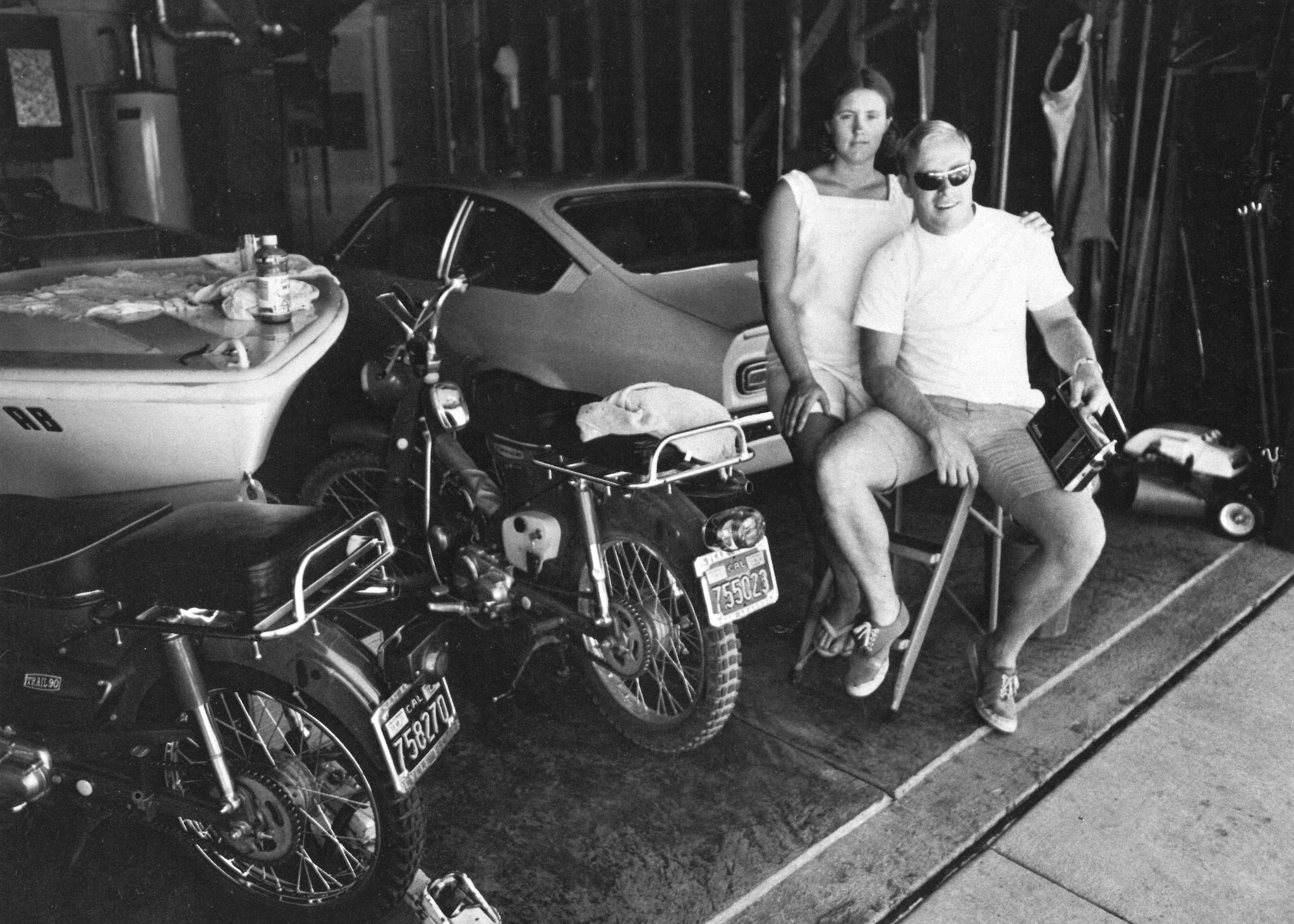

In 1968, thirty-odd miles east of Silicon Valley and Stanford University, Bill Owens began working as a photographer for the Livermore Independent. It’s during this time that Owens produced the photographs that would become Suburbia. Lauded as “one of the most original and important books in late-20th-century photography,” Suburbia captures both the banalities and eccentricities of what seems to be the average American new development.

Located at the east end of Livermore is the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The laboratory was co-founded by Edward Teller and Ernest Lawrence as an offshoot of the University of California Radiation Laboratory at Berkely. Livermore was chosen as the site for the new laboratory because it would provide greater security for classified projects. When seventy-five Berkeley lab employees arrived in Livermore on September 2, 1952, Livermore was a quiet agricultural and ranching town of 4,000.

Since its inception, Livermore has been responsible for the development and maintenance of the United States’ nuclear weapons. By the time Owens published Suburbia, Edward Teller had led the lab to overtake Los Alamos in the development of nuclear weapons by relying heavily on computer simulations and a more experimental approach to warhead design. Between the lab's founding in 1952 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the lab developed warheads for artillery shells, strategic bombs, intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles including the W87 and B83 warheads that are still in the U.S. nuclear stockpile today.

As Owens arrived in Livermore, the laboratory’s laser fusion program was ramping up with support from the Atomic Energy Commision. In 1974, the lab built Janus, the first of a series of lasers designed to test inertial confinement fusion for national security applications. Janus was followed by Cyclops in 1975, Argus in 1976 and Shiva in 1977.

During the same period, the lab’s National Magnetic Fusion Energy Computer Center began taking delivery of a series of Cray supercomputers. The Cray supercomputers were a continuation of the lab’s use of state of the art computers that began with a UNIVAC system in 1953. Much of modern day computing and software has its origins in the Livermore Radiation Lab including the use of large-scale, networked time-sharing with the lab’s Octopus network connecting hundreds of remote terminals and printers to the central, shared computers. The lab has remained at the cutting edge of computing power and in 2024 the laboratory’s El Capitan became the fastest supercomputer in the world.

Despite being the largest employer in the town—with Sandia National Laboratory the second largest employer—and the cornerstone of the United State’s nuclear weapons program, the laboratory is mentioned only once in Suburbia. Under an image of two men running is the caption,

My job as an engineer at Lawrence Radiation Laboratory causes a certain amount of tension and frustration. By running a few miles each day I’m able to find a new sense of being. I love running.

While there is no doubt that Suburbia reflects a larger truth about the “post-World War II housing boom and the rapid migration from the inner-city to affordable, mass-produced homes in city outskirts,” Owens’ work only becomes more revelatory with the knowledge of the population he is depicting.

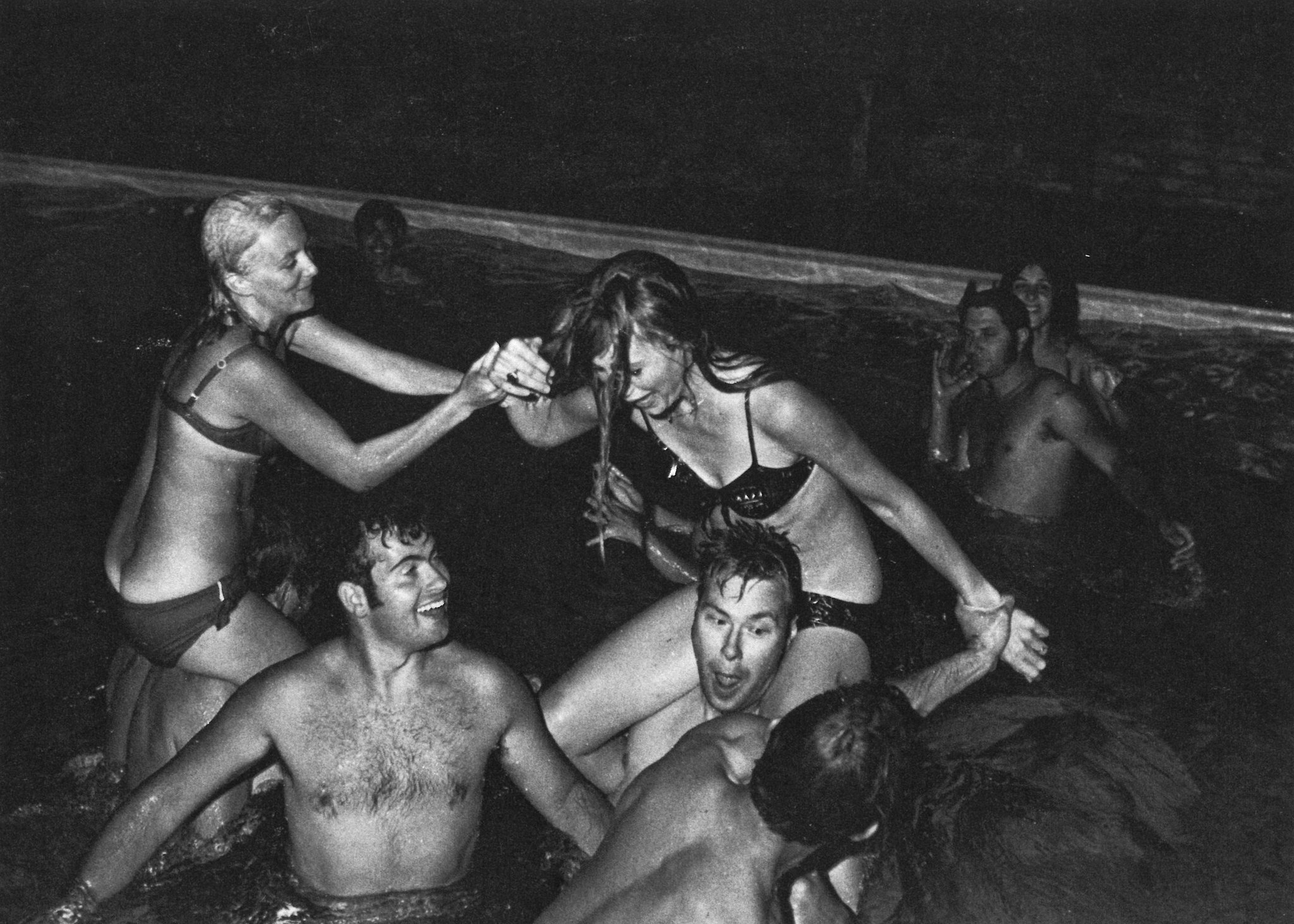

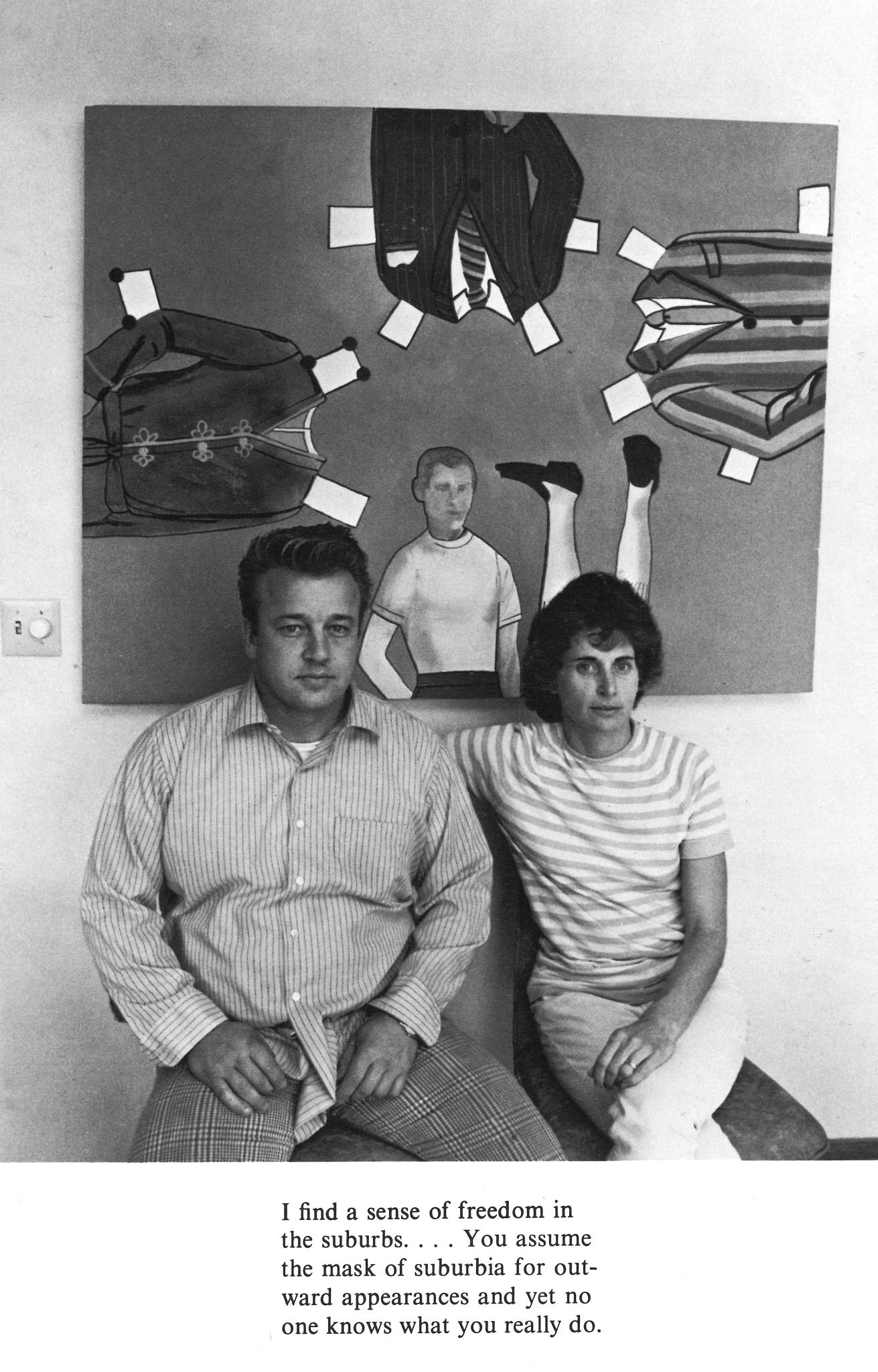

An image of a middle aged couple seated beneath a painting of paper doll clothes—the woman looking into the camera and the man staring disassociatedly into the distance—is captioned, “I find a sense of freedom in the suburbs . . . You assume the mask of suburbia for outward appearances and yet no one knows what you really do.” Lewis Baltz, who was also working in California during the same period of explosive development, said of his 1974 project, The new Industrial Parks near Irvine, California, “You don’t know whether they’re manufacturing pantyhose or megadeath.” Megadeath, it turns out, was better hidden in Owens’ humorous and empathetic portraits of his friends in Livermore than in Baltz’s faceless warehouses.

Owens continued to work in Livermore—including a small number of photogrpaphs taken at the lab—until giving up photography for a more lucrative career in craft brewing and distilling. His Livermore work includes Suburbia (1973), Our Kind of People: American Groups and Rituals (1975), Working (I Do It for the Money) (1977), Leisure (2005), and Altamont 1969 (2019).

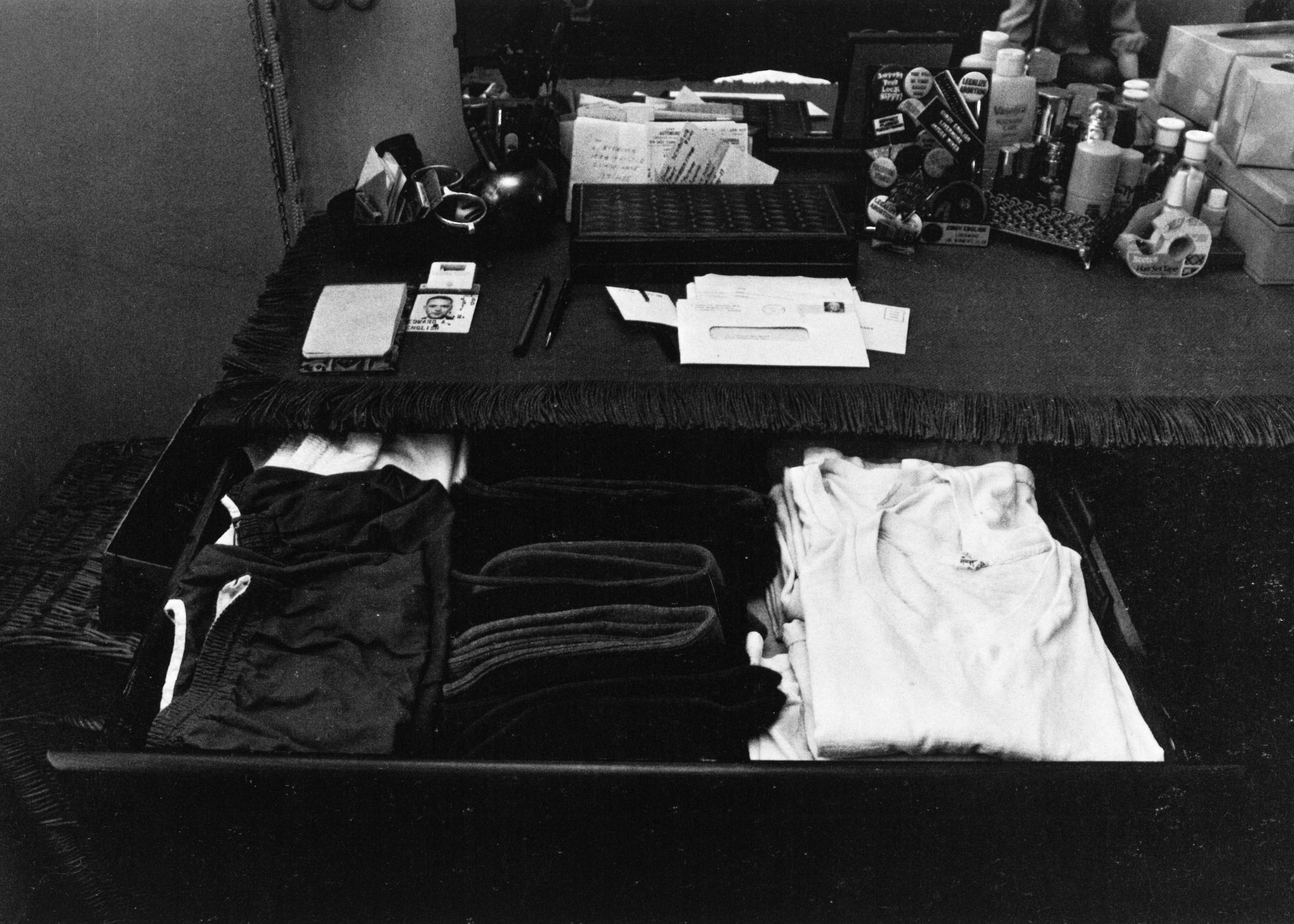

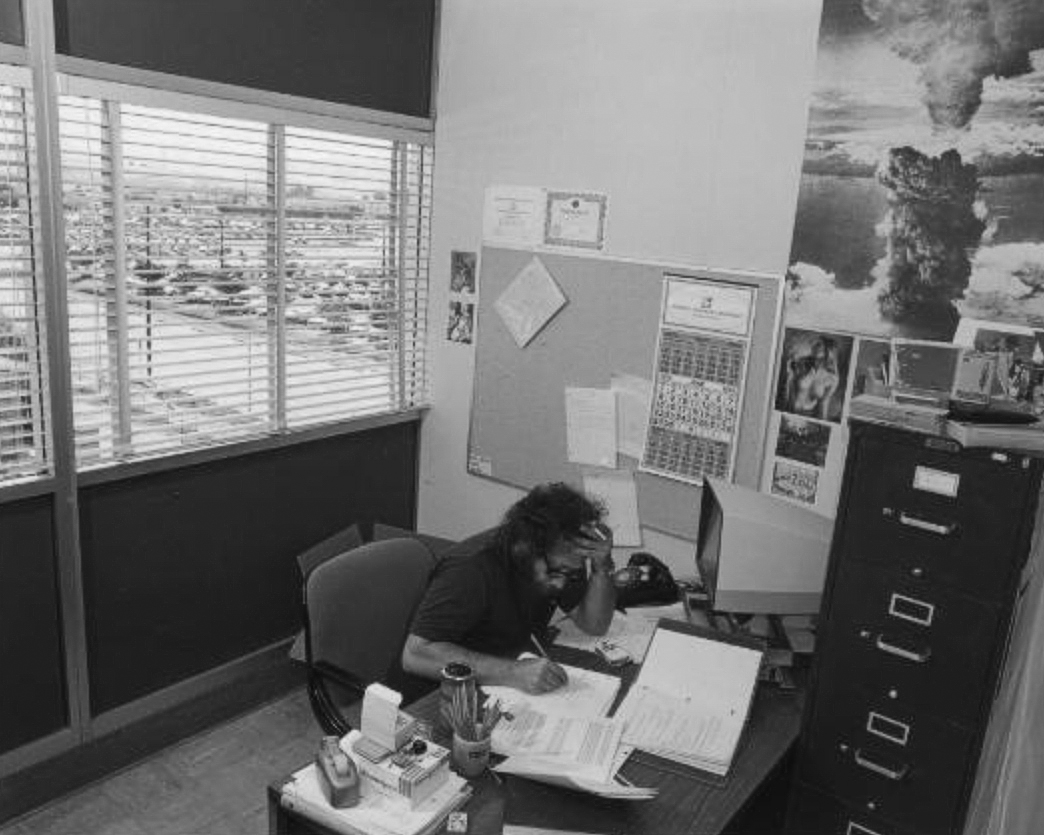

Lawrence Livermore Lab, Livermore, California, Working, 1976

Lawrence Livermore Lab, Livermore, California, Working, 1976

John Birch Society, Our Kind of People, 1975

John Birch Society, Our Kind of People, 1975

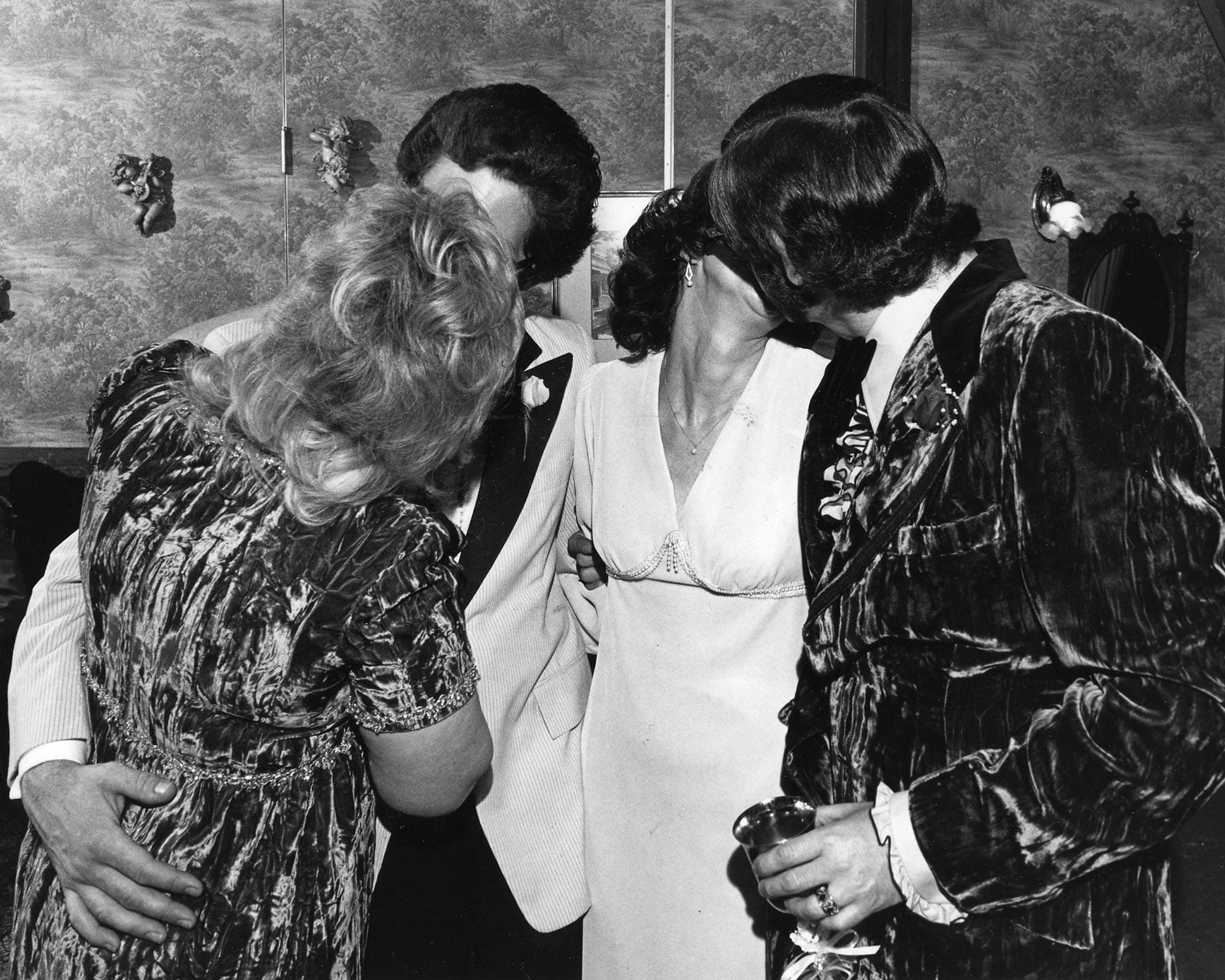

Swingers, Our Kind of People, 1975

Swingers, Our Kind of People, 1975

Freemasons, Our Kind of People, 1975

Freemasons, Our Kind of People, 1975

— C. B.